Retecool verzamelt de cartoons over Charlie Hebdo

Veel terugkerende thema’s, maar een goede verzameling.

De afgelopen week waren er twee gevallen van Palestijnse vrouwen, meisjes eigenlijk meer, die werden beschuldigd van het uitvoeren van een aanval met een mes, of het dreigen met een mes. De 22-jarige Amal Jihad Taqatqa uit het dorp Beit Fajjar bij Bethlehem werd ervan beschuldigd dat ze op maandag 1 december een man zou hebben aangevallen en gestoken met een mes bij een bushalte bij het nederzettingenblok Gush Etzion. De man werd heel licht aan de schouder gewond. Amal Taqatqa werd echter meteen neergeschoten door een wachter bij de ingang van een nederzetting en daarna, nadat ze gewond op de grond lag, nog eens door tenminste vier soldaten van enige afstand onder schot genomen. Dat overleefde ze natuurlijk niet. Ze werd zwaar gewond naar een ziekenhuis vervoerd en is inmiddels overleden. Een tweede geval betrof de zestienjarige Yathriv Salah Rayyan uit Beit Duqqu bij Jeruzalem. Zij werd op 5 december overmeesterd toen ze de verkeerde toegangsweg (die voor auto's) nam bij het Qalandiya checkpoint en daar, naar wordt gezegd, met een mesje dreigde. Het is zeker niet voor het eerst dat vrouwen op de Westoever op een dergelijke manier in het nieuws komen. In Israël wordt dat gezien als een bewijs van het bloeddorstige karakter van Palestijnse vrouwen: Zie je wel, wordt er dan gezegd, ze zijn geen haar beter dan de mannen. Enige navraag op de Westoever bij mensen die wel eens te maken hebben met Palestijnen die in aanraking met justitie komen, leert echter dat vaak heel andere redenen een rol spelen.

Veel terugkerende thema’s, maar een goede verzameling.

Bedrieglijk echt gaat over papyrologie en dan vooral over de wedloop tussen wetenschappers en vervalsers. De aanleiding tot het schrijven van het boekje is het Evangelie van de Vrouw van Jezus, dat opdook in het najaar van 2012 en waarvan al na drie weken vaststond dat het een vervalsing was. Ik heb toen aangegeven dat het vreemd was dat de onderzoekster, toen eenmaal duidelijk was dat deze tekst met geen mogelijkheid antiek kon zijn, beweerde dat het lab uitsluitsel kon geven.

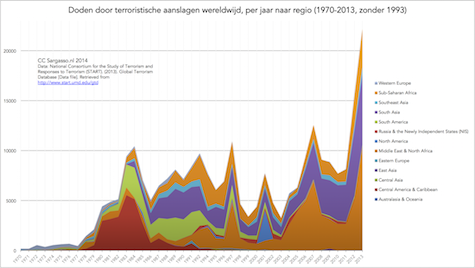

DATA - Aantal doden door terroristische aanslagen gestegen, aldus het nieuws vandaag. Goed moment om onze rapportage vanuit de grote globale terrorisme database te actualiseren. De situatie in 2013 bleek nog ernstiger dan al eerder gerapporteerd.

Eerst het aantal dodelijke slachtoffers. Nu naar regio.

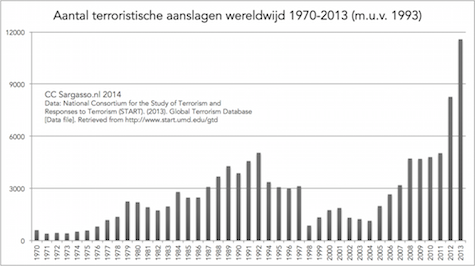

Ook als je alleen naar het aantal aanslagen per jaar kijkt is het beeld weinig hoopgevend.

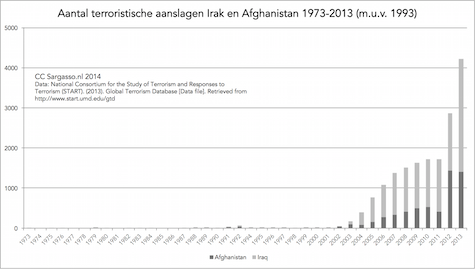

Groot deel van de stijging is echter voor rekening van Irak en Afghanistan.

De “War on Terrorism” begon na de aanslag in 2001. De twee grootste “slagen” die uitgedeeld werden waren in Afghanistan en Irak. Ergens lijkt er iets niet te kloppen in de aanpak.

NB data van:

National Consortium for the Study of Terrorism and Responses to Terrorism (START). (2013). Global Terrorism Database [Data file]. Retrieved from http://www.start.umd.edu/gtd

Tot het eind van de Koude Oorlog heeft de BVD de CPN in de gaten gehouden. Maar de dienst deed veel meer dan spioneren. Op basis van nieuw archiefmateriaal van de AIVD laat dit boek zien hoe de geheime dienst in de jaren vijftig en zestig het communisme in Nederland probeerde te ondermijnen. De BVD zette tot tweemaal toe personeel en financiële middelen in voor een concurrerende communistische partij. BVD-agenten hielpen actief mee met geld inzamelen voor de verkiezingscampagne. De regering liet deze operaties oogluikend toe. Het parlement wist van niets.

In Parijs zijn woensdag Twaalf doden en enkele gewonden gevallen toen met een automatisch wapen werd geschoten in het kantoor van het Franse satirische weekblad Charlie Hebdo.

Sargasso is een laagdrempelig platform waarop mensen kunnen publiceren, reageren en discussiëren, vanuit de overtuiging dat bloggers en lezers elkaar aanvullen en versterken. Sargasso heeft een progressieve signatuur, maar is niet dogmatisch. We zijn onbeschaamd intellectueel en kosmopolitisch, maar tegelijkertijd hopeloos genuanceerd. Dat betekent dat we de wereld vanuit een bepaald perspectief bezien, maar openstaan voor andere zienswijzen.

In de rijke historie van Sargasso – een van de oudste blogs van Nederland – vind je onder meer de introductie van het liveblog in Nederland, het munten van de term reaguurder, het op de kaart zetten van datajournalistiek, de strijd voor meer transparantie in het openbaar bestuur (getuige de vele Wob-procedures die Sargasso gevoerd heeft) en de jaarlijkse uitreiking van de Gouden Hockeystick voor de klimaatontkenner van het jaar.

Zo meldt, althans, de openbaar aanklager van de Franse stad:

De 40-jarige man bekende maandag verantwoordelijk te zijn voor de aanrijding. Hij werd in totaal 157 keer opgenomen met psychische klachten sinds 2001. De laatste keer was deze herfst.

De man handelde alleen en had geen religieuze motieven. Volgens omstanders riep de man ten tijde van de aanrijding “God is groot” (Allahoe Akbar). Dit zou hij gedaan hebben om zichzelf moed te geven en niet vanuit religieuze overtuigingen, aldus de Franse justitie.

De gijzelnemer in Sydney, die geïnspireerd was door het radicale gedachtegoed van IS, had issues:

De radicale geestelijke Man Haron Monis was in 1996 van Iran naar Australië gevlucht. Haron Monis was een bekende van de politie. Begin dit jaar moest hij voor de rechter verschijnen op verdenking van medeplichtigheid aan de moord op zijn ex-vrouw. Die werd neergestoken en in brand gestoken in een trappenhuis in Werrington.

In die zaak verdedigde hij zichzelf. Hij beweerde dat de Australische AIVD, de ASIO, hem middels een complot in de gevangenis wil krijgen. Ook zou hij eerder zijn veroordeeld voor het sturen van haatbrieven aan nabestaanden van Australische militairen die bij internationale operaties zijn gesneuveld.

[…]In oktober werd een zaak tegen hem begonnen, omdat hij ruim tien jaar terug tientallen vrouwen zou hebben aangerand tijdens zijn werk als alternatief genezer die zwarte magie beoefende. De man zou zichzelf tot sjeik Haron hebben benoemd.

Vrijdag zou de zelfbenoemde sjeik nog een laatste, wanhopige poging hebben gedaan bij het hooggerechtshof om de aanklachten tegen hem te laten vervallen.

Een longread uit de Guardian. Martin Chulov verhaalt over het ontstaan van het leiderschap van IS en andere Soennitische bewegingen in Iraq en Syrië.

Onze ultieme vijanden hebben zich grotendeels tijdens Amerikaanse detentie weten te organiseren, juist dankzij de relatieve veiligheid die dat bood:

If there was no American prison in Iraq, there would be no IS now. Bucca [Prison] was a factory. It made us all. It built our ideology.

A decade of fear-mongering has brought power and wealth to those who have been the most skillful at hyping the terrorist threat. Fear sells. Fear has convinced the White House and Congress to pour hundreds of billions of dollars – more money than anyone knows to do with – into counterterrorism and homeland security programs, often with little management or oversight, and often to the detriment of the Americans they are supposed to protect. Fear is hard to question. It is central to the financial well-being of countless federal bureaucrats, contractors, subcontractors, consultants, analysts, and pundits. Fear generates funds.

ANALYSE - Dit stuk van John Oliver is alweer een paar weken oud. Maar daarmee niet minder relevant. Hij maakt scherp duidelijk dat het onderwerp nauwelijks in het nieuws is, maar dat er steeds meer inzet van drones is en dat er steeds meer, vaak onschuldige, mensen sterven. Zo vaak dat de jeugd in landen zoals Pakistan angstig worden als de lucht blauw is, want dan is de kans op een drone aanval het grootst.

The executive branch has the right to kill anyone, anywhere on the world, anytime, for secret reasons based on secret evidence in a secret proces undertaken by unidentified officials

Uit een lezenswaardig stuk in The New Yorker:

If military and political interference is such a dominant driving force in terrorism, why aren’t these kinds of attacks more common? Out of the more than one million Canadian Muslims, only a handful have committed terrorist acts, and fewer than a hundred people are being actively monitored by Canadian authorities as likely to join in terrorist activities abroad. Something more is obviously often at work.

Rather than hastily framing attacks in the context of a battle between the West and the Muslim world, it may be more productive, in terms of diagnosis and prevention, to look at more profiles of self-styled ISIS fellow-travelers who commit attacks as individuals. What we know of Zehaf-Bibeau’s biography offers some instructive clues. According to reports published in the Globe and Mail and elsewhere, he had a history of mental illness and of run-ins with the law, involving drug possession, theft, and making threats. He battled an addiction to crack cocaine and, in the weeks leading up to the attack, he was living in a homeless shelter. Dave Bathurst, a friend of Zehaf-Bibeau and himself a Muslim, told the Globe, “We were having a conversation in a kitchen, and I don’t know how he worded it: He said the devil is after him.” Bathurst said his friend often spoke of the presence of shaytan—the Arabic term for devils and demons. “I think he must have been mentally ill.”

According to Dr. Thomas Hegghammer, the director of terrorism research at the Norwegian Defence Research Establishment, Zehaf-Bibeau fits a profile of “converts with a history of delinquency among the Westerners in ISIL. He’s a little older than average; otherwise, there is nothing unusual about his profile.” Conversion to Islam itself isn’t a cause of violence, as we well know […]. What seems to be the problem, rather, is the fusion of radical jihadist ideology with other personal problems, whether they be alienation, anomie, or various shades of mental illness. In a world where “clash of civilizations” rhetoric is pervasive, it is possible that radical Islam offers the same appeal to some unstable individuals that anarchism had for Leon Czolgosz, who killed President William McKinley in 1901, and that Marxism had for Lee Harvey Oswald. If you are alienated from the existing social order, the possibility of joining, even as a “lone wolf” killer, any larger social movement that promises to overturn that society may be attractive. For a person radicalized in this manner, the fantasy of political violence is a chance to gain agency, make history, and be part of something larger.

Op een vroege zomerochtend loopt de negentienjarige Simone naakt weg van haar vaders boerderij. Ze overtuigt een passerende automobiliste ervan om haar mee te nemen naar een afgelegen vakantiehuis in het zuiden van Frankrijk. Daar ontwikkelt zich een fragiele verstandhouding tussen de twee vrouwen.

Wat een fijne roman is Venus in het gras! Nog nooit kon ik zoveel scènes tijdens het lezen bijna ruiken: de Franse tuin vol kruiden, de schapen in de stal, het versgemaaide gras. – Ionica Smeets, voorzitter Libris Literatuurprijs 2020.